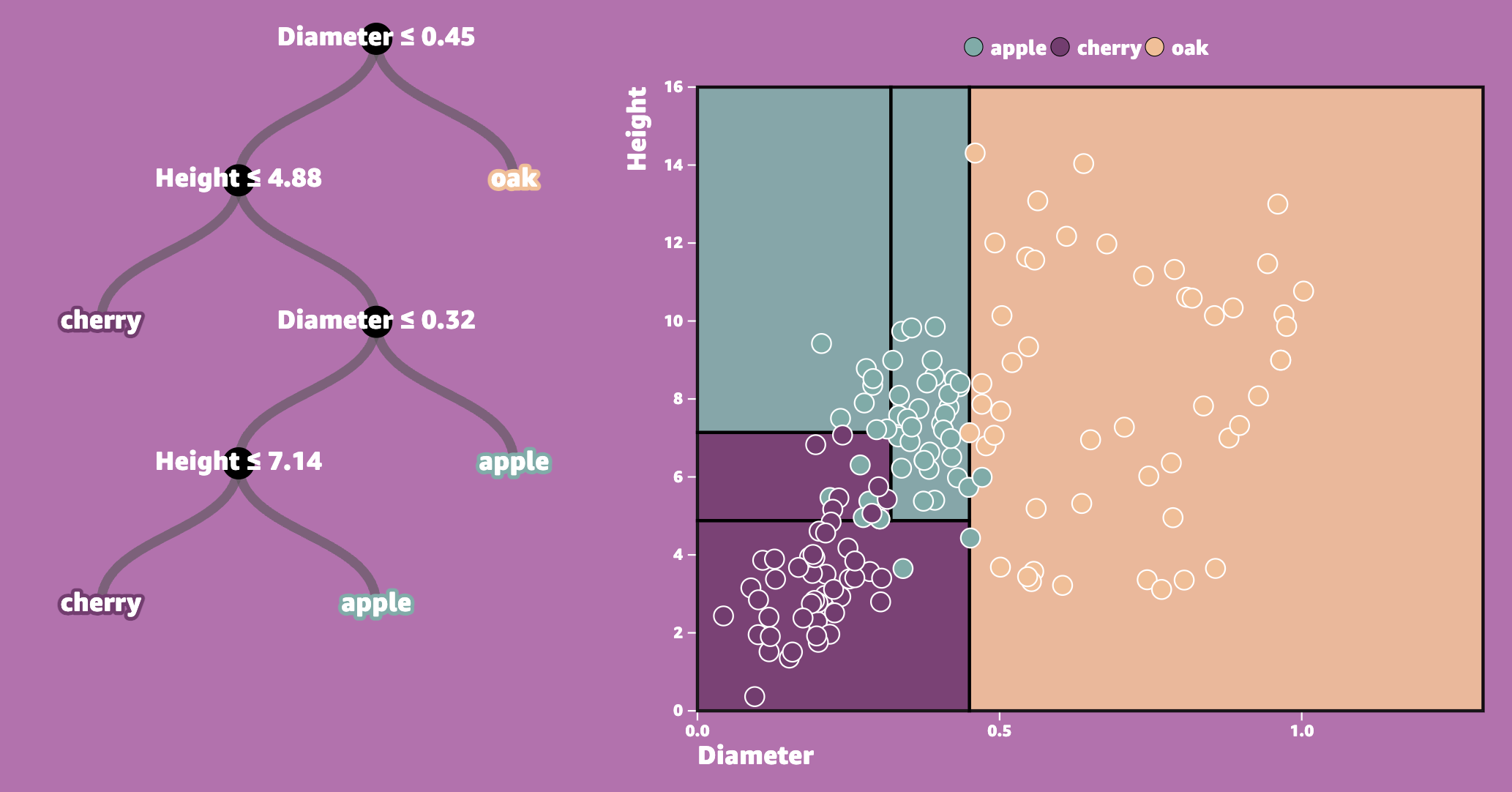

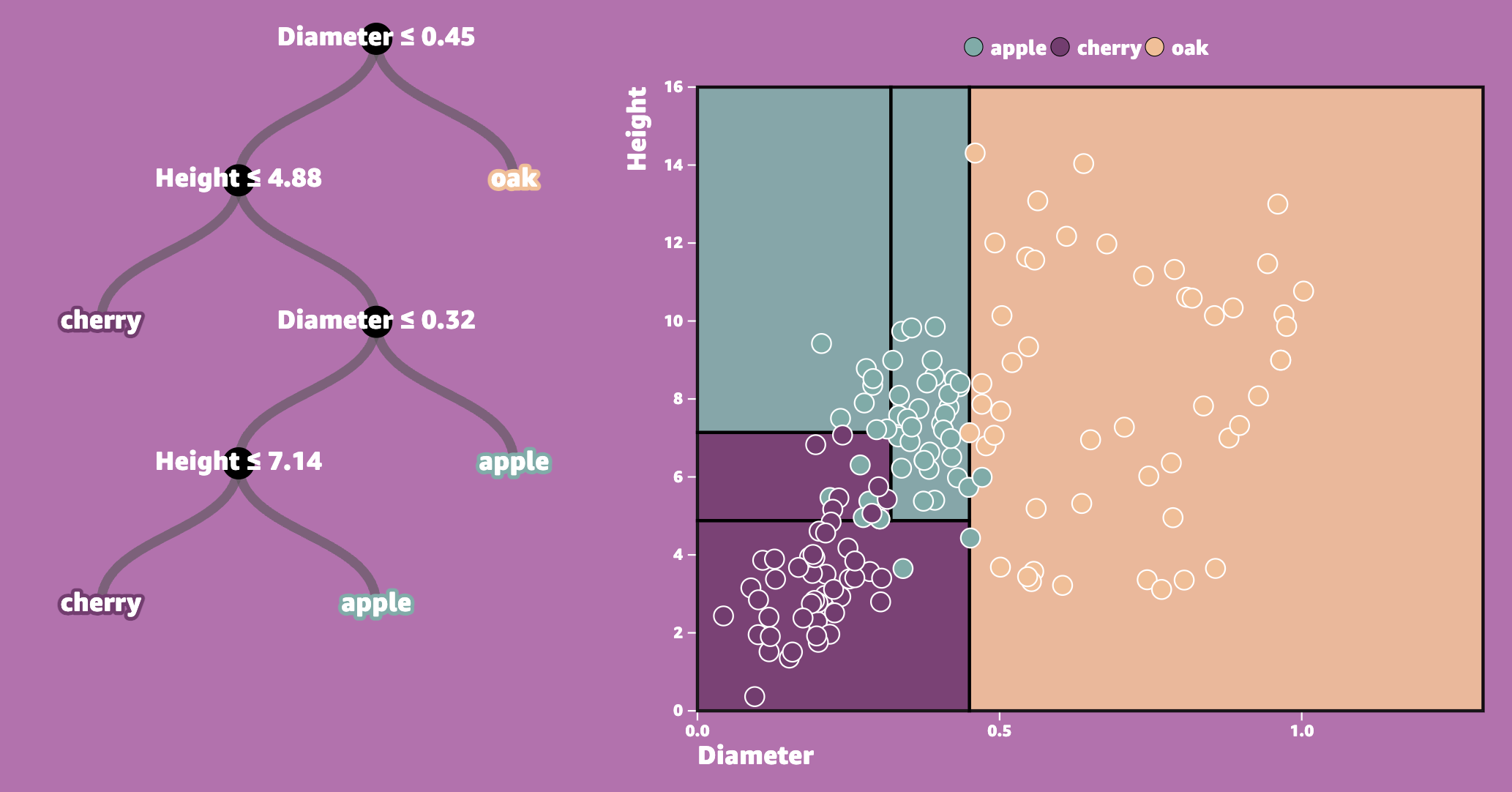

Tree-based and ensemble models

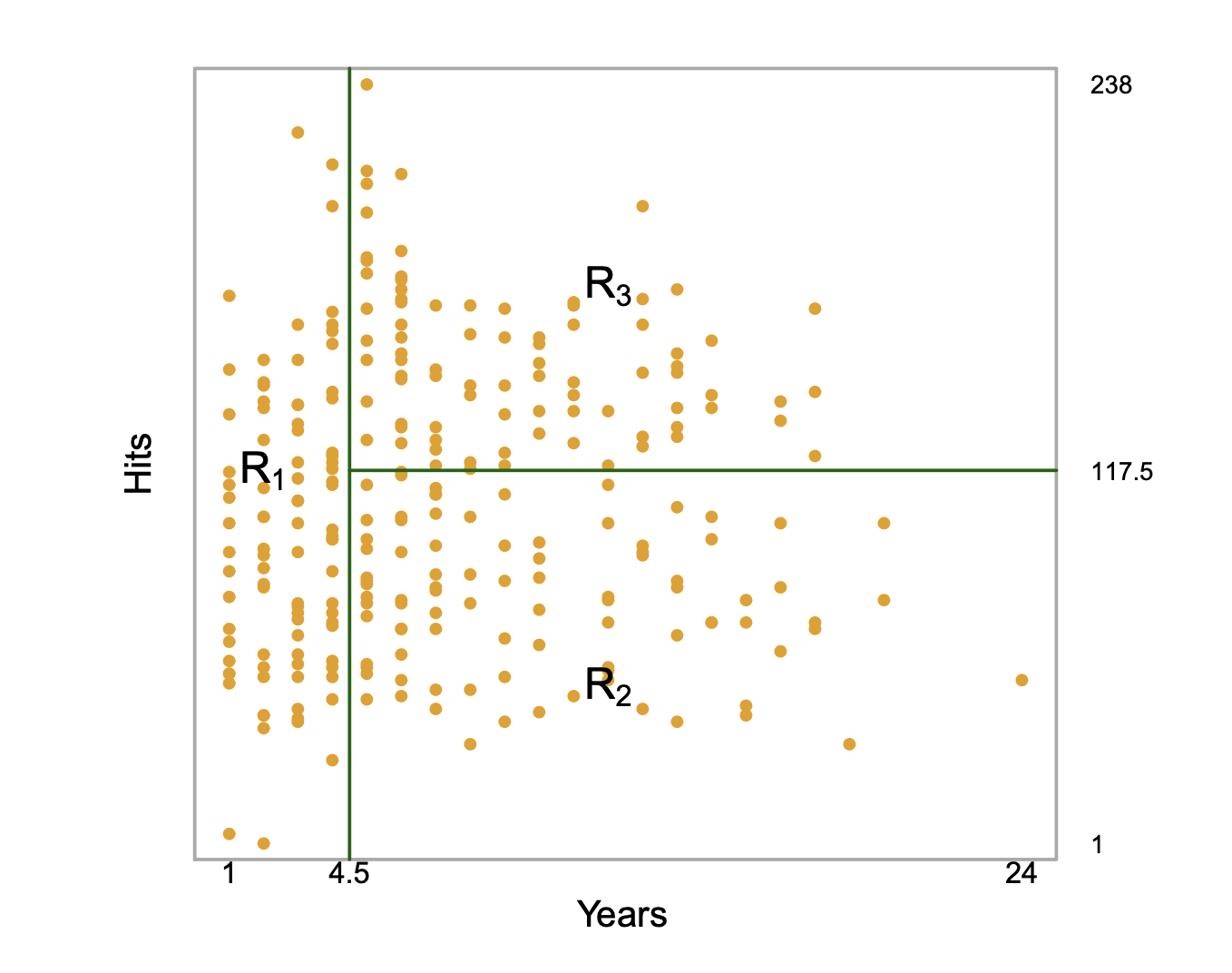

Tree-based methods

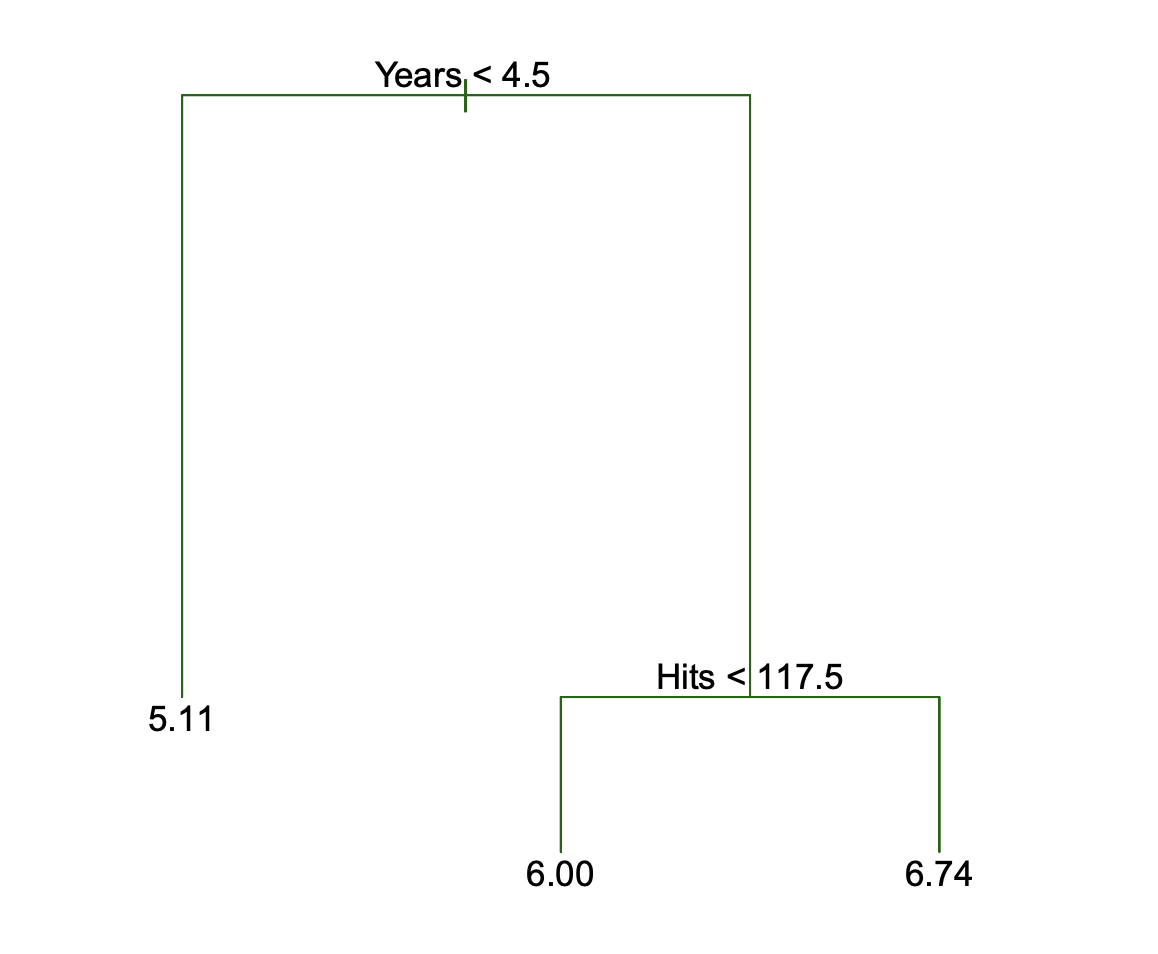

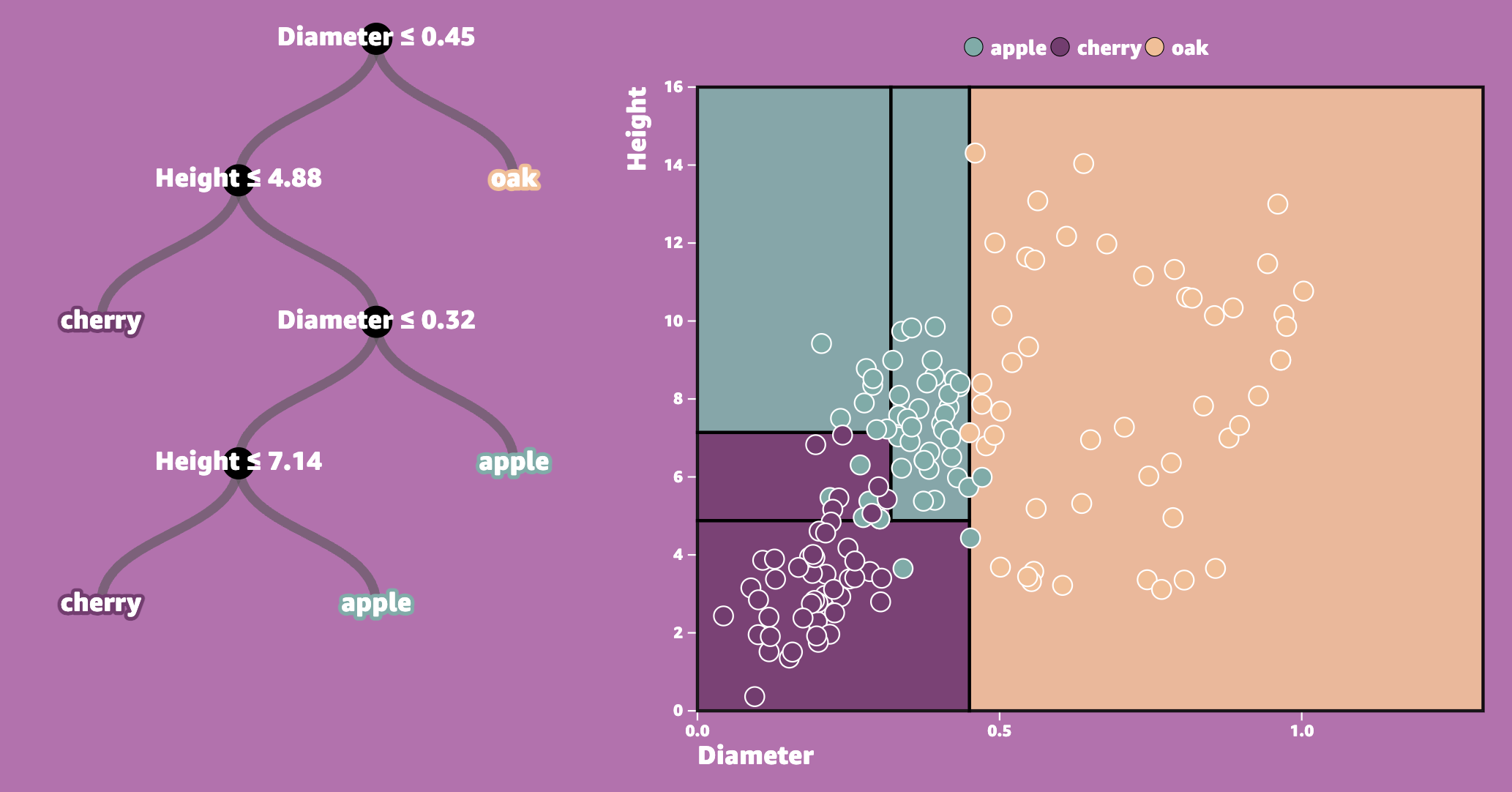

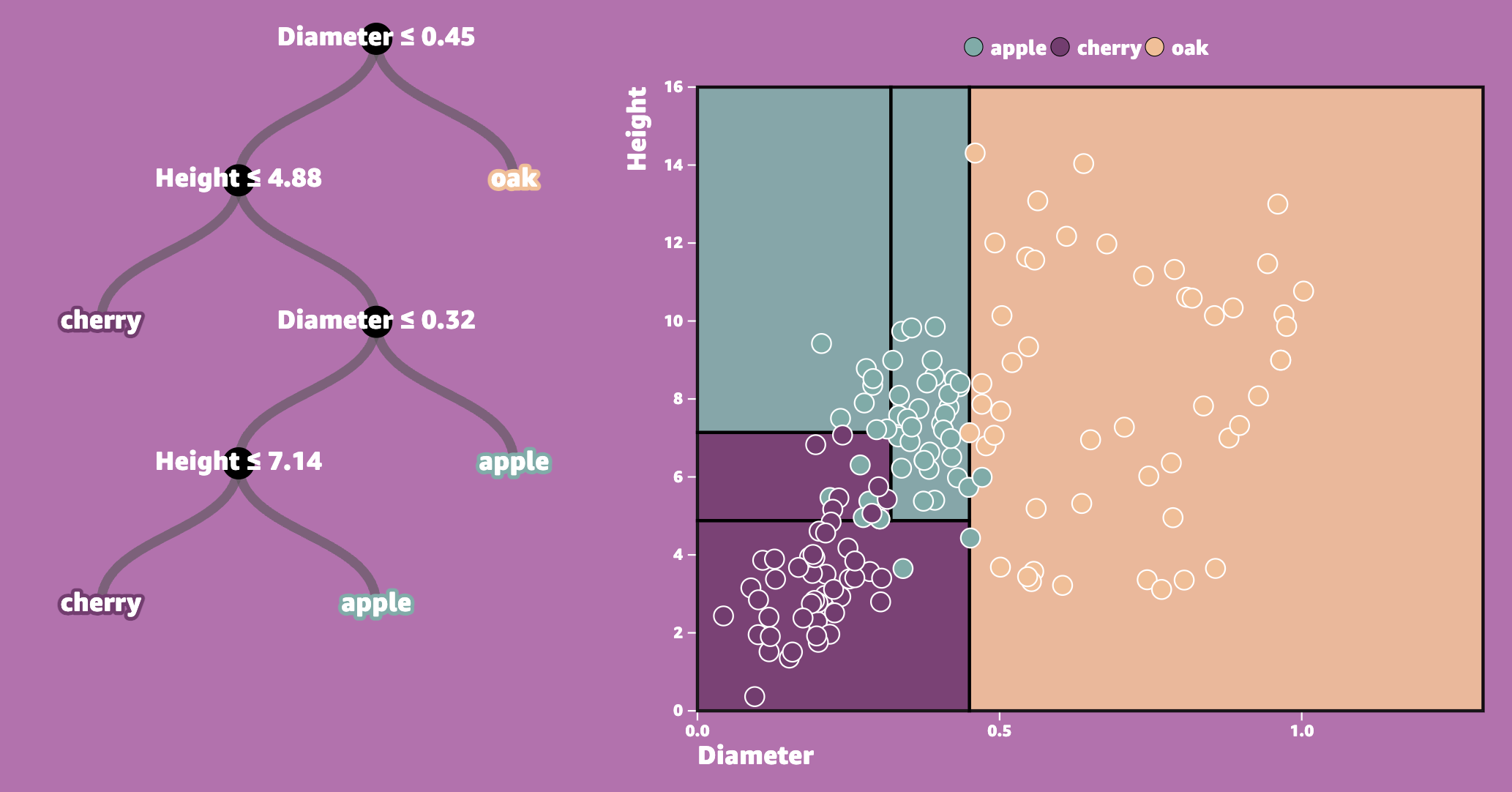

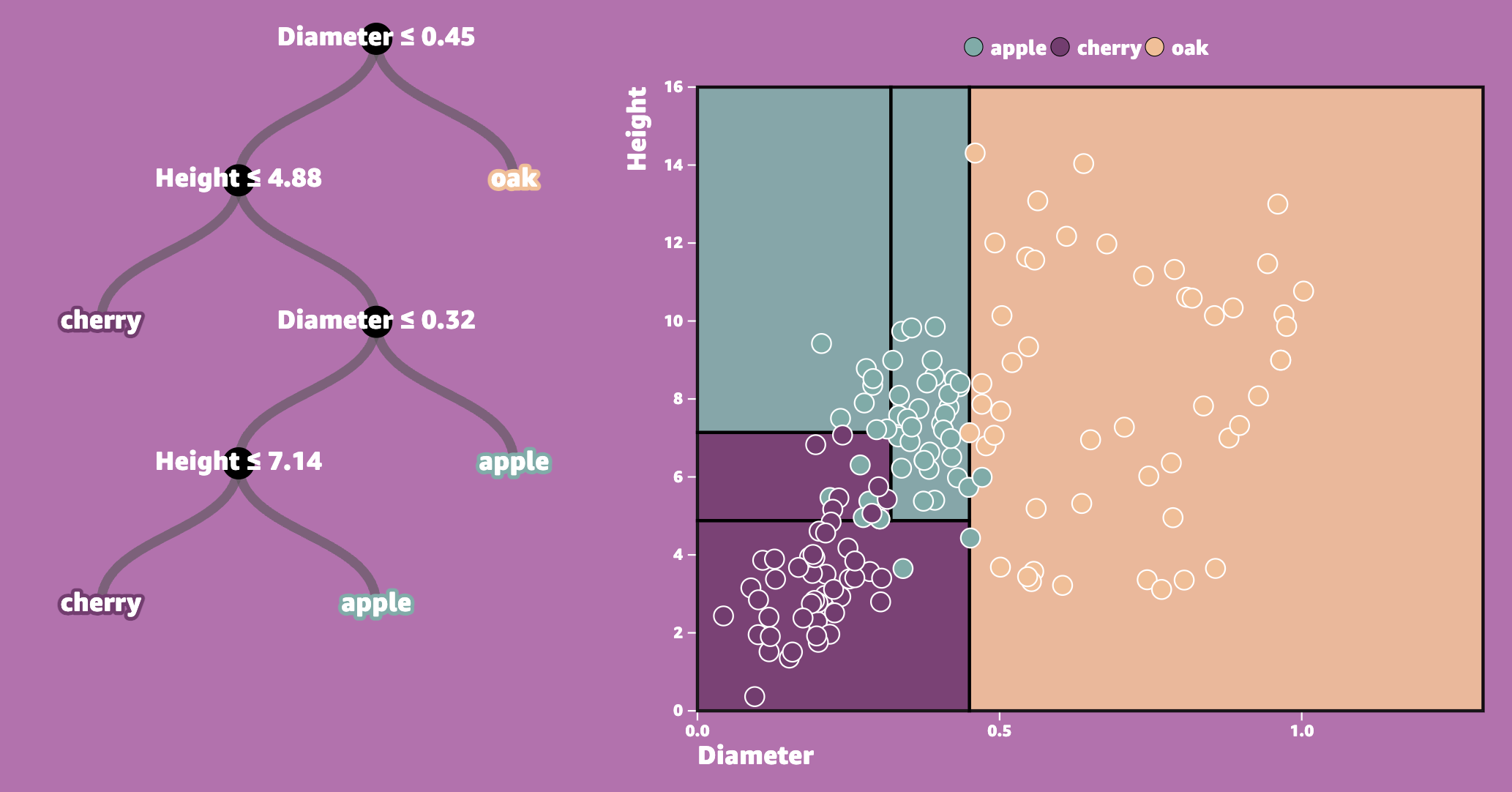

Algorithms that segment the predictor space into a number of simple regions.

Named decision trees because they can be summarized as a tree.

Source: An Introduction to Statistical Learning with Applications in Python by James, Witten, Hastie, Tibshirani & Taylor

Tree-based methods

Decision trees on their own, are very explainable and intuitive, but not very powerful at predicting.

However, there are extensions of decision trees, such as random forest and boosted trees, which are very powerful at predicting. We will demonstrate two of these in this session.

Decision trees

- Excellent decision Trees explainer web app by Jared Wilber & Lucía Santamaría

Classification Decision trees

- Use recursive binary splitting to grow a classification tree (splitting of the predictor space into \(J\) distinct, non-overlapping regions).

Classification Decision trees

- For every observation that falls into the region \(R_j\) , we make the same prediction, which is the majority vote for the training observations in \(R_j\).

Classification Decision trees

- Where to split the predictor space is done in a top-down and greedy manner, and in practice for classification, the best split at any point in the algorithm is one that minimizes the Gini index (a measure of node purity).

Classification Decision trees

- A limitation of decision trees is that they tend to overfit, so in practice we use cross-validation to tune a hyperparameter, \(\alpha\), to find the optimal, pruned tree.

Example: the heart data set

Let’s consider a situation where we’d like to be able to predict the presence of heart disease (

AHD) in patients, based off 13 measured characteristics.The heart data set contains a binary outcome for heart disease for patients who presented with chest pain.

Example: the heart data set (cont’d)

An angiographic test was performed and a label for AHD of Yes was labelled to indicate the presence of heart disease, otherwise the label was No.

Do we have a class imbalance?

It’s always important to check this, as it may impact your splitting and/or modeling decisions.

Data splitting

Let’s split the data into training and test sets:

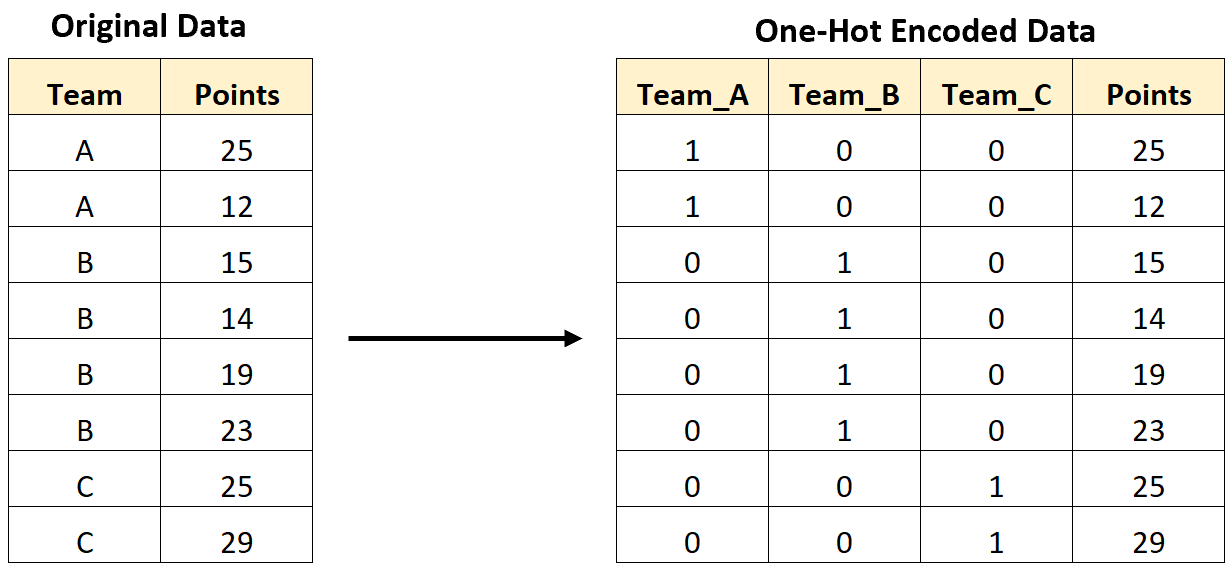

Categorical variables

This is our first case of seeing categorical predictor variables, can we treat them the same as numerical ones? No!

In

scikit-learnwe must perform one-hot encoding

Look at the data again

Which columns do we need to standardize?

Which do we need to one-hot encode?

One hot encoding & pre-processing

handle_unknown = "ignore"handles the case where categories exist in the test data, which were missing in the training set. Specifically, it sets the value for those to 0 for all cases of the category.

Fitting a dummy classifier

Put the mean cross-validated error in a data frame

Fitting a decision tree

Add the mean cross-validated error to our results data frame

Can we do better?

We could tune some decision tree parameters (e.g., alpha, maximum tree depth, etc)…

We could also try a different tree-based method!

Another great explainer: the Random Forest Algorithm by Jenny Yeon & Jared Wilber

The Random Forest Algorithm

Build a number of decision trees on bootstrapped training samples.

When building the trees from the bootstrapped samples, at each stage of splitting, the best splitting is computed using a randomly selected subset of the features.

Take the majority votes across all the trees for the final prediction.

Random forest in scikit-learn

Add the mean cross-validated error to our results data frame

Can we do better?

Random forest can be tuned a several important parameters, including:

n_estimators: number of decision trees (higher = more complexity)max_depth: max depth of each decision tree (higher = more complexity)max_features: the number of features you get to look at each split (higher = more complexity)

We can use

GridSearchCVto search for the optimal parameters for these, as we did for \(K\) in \(K\)-nearest neighbors.

Tuning random forest in scikit-learn

Comparing to our other models

How did the tuned Random Forest compare against the other models we tried?

Boosting

No randomization.

The key idea is combining many simple models called weak learners, to create a strong learner.

They combine multiple shallow (depth 1 to 5) decision trees.

They build trees in a serial manner, where each tree tries to correct the mistakes of the previous one.

Tuning Boosted Classifiers

HistGradientBoostingClassifiercan be tuned a several important parameters, including:max_iter: number of decision trees (higher = more complexity)max_depth: max depth of each decision tree (higher = more complexity)learning_rate: the shrinkage parameter which controls the rate at which boosting learns. Values between 0.01 or 0.001 are typical.

We can use

GridSearchCVto search for the optimal parameters for these, as we did for the parameters in Random Forest.

Tuning Boosted Classifiers (cont’d)

Boosted Classifiers results

How did the HistGradientBoostingClassifier compare against the other models we tried?

How do we choose the final model?

Remember, what is your question or application?

A good rule when models are not very different, what is the simplest model that does well?

Look at other metrics that are important to you (not just the metric you used for tuning your model), remember precision & recall, for example.

Remember - no peaking at the test set until you choose! And then, you should only look at the test set for one model!

Precision and recall

Precision and recall cont’d

What do we think? Is this model ready for production in a diagnostic setting?

How could we improve it further?

Feature importances: key points

Decision trees are very interpretable (decision rules!), however in ensemble models (e.g., Random Forest and Boosting) there are many trees - individual decision rules are not as meaningful…

Instead, we can calculate feature importances as the total decrease in impurity for all splits involving that feature, weighted by the number of samples involved in those splits, normalized and averaged over all the trees.

These are calculated on the training set, as that is the set the model is trained on.

Feature importances: Notes of caution!

Feature importances can be unreliable with both highly cardinal, and multicollinear features.

Unlike the linear model coefficients, feature importances do not have a sign! They tell us about importance, but not an “up or down”.

Increasing a feature may cause the prediction to first go up, and then go down.

Alternatives to feature importance to understanding models exist, such as post-hoc explanations (sometimes called “explainable AI”, see Interpretable Machine Learning by Christoph Molnar for an introduction)

Feature importances in scikit-learn

Feature importances in scikit-learn (cont’d)

Visualizing the results

Visualizing the results

Evaluating on the test set

Predict on the test set:

Evaluating on the test set

Examine accuracy, precision and recall:

Evaluating on the test set

Keep learning!

Local installation

Using Docker: Data Science: A First Introduction (Python Edition) Installation Instructions

Using conda: UBC MDS Installation Instructions

Additional resources

- The UBC DSCI 573 (Feature and Model Selection notes) chapter of Data Science: A First Introduction (Python Edition) by Varada Kolhatkar and Joel Ostblom. These notes cover classification and regression metrics, advanced variable selection and more on ensembles.

- The

scikit-learnwebsite is an excellent reference for more details on, and advanced usage of, the functions and packages in the past two chapters. Aside from that, it also offers many useful tutorials to get you started. - An Introduction to Statistical Learning {cite:p}

james2013introductionprovides a great next stop in the process of learning about classification. Chapter 4 discusses additional basic techniques for classification that we do not cover, such as logistic regression, linear discriminant analysis, and naive Bayes.

References

Gareth James, Daniela Witten, Trevor Hastie, Robert Tibshirani and Jonathan Taylor. An Introduction to Statistical Learning with Applications in Python. Springer, 1st edition, 2023. URL: https://www.statlearning.com/.

Kolhatkar, V., and Ostblom, J. (2024). UBC DSCI 573: Feature and Model Selection course notes. URL: https://ubc-mds.github.io/DSCI_573_feat-model-select

Pedregosa, F. et al., 2011. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. Journal of machine learning research, 12(Oct), pp.2825–2830.

Questions?